How would you feel if we told you that your head is covered in squiggles? Don’t worry; it’s not just you. This is something that is true for all human skulls. Also, you don’t have to be too embarrassed about them as nobody can see the lines because your scalp is covering them.

How Skulls Are Formed

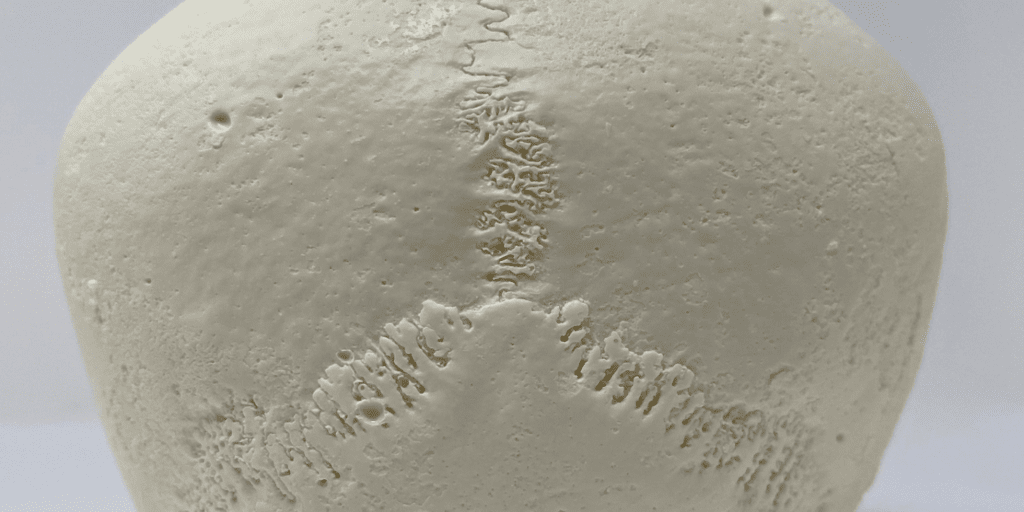

As human skulls are made up of numerous different bones that fuse together rather than just one, there are squiggly lines on it that form over time. These lines are known as sutures. They are referred to as “cranial sutures” because “squiggly lines” is not a legitimate scientific term. There is a total of four, two of which are on the top of our skulls, one crosses the top in the middle, and the other effectively “crosses the T” with it lying over the breadth of the skulls.

The bones in our heads aren’t exactly lined up properly when we are born, which actually helps the infant go more easily through the birth canal, but when the baby is born, the bones begin to fuse together. Because the skull’s bones are not fused, the skull’s plates can compress and overlap more easily during birth and expand more quickly to accommodate the baby’s rapid brain development.

As a result, the skull’s bones haven’t completely cemented together, which is why newborns have two “soft patches” on their heads. It resembles the peculiar stitch that appears when two previously separate pieces fuse together and leave a mark indicating the location of the joining point.

An Ancient Investigation

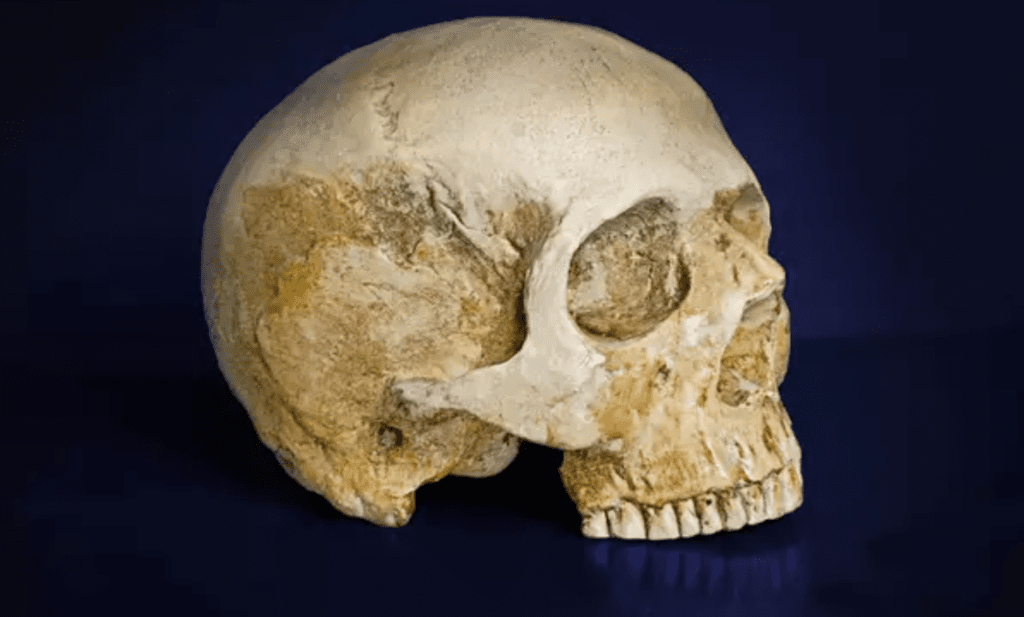

In order to understand more about the environment in which our brains reside, significant study on human skulls is still being done today. Recently, a group of experts working to investigate a 34-person crime that happened 5,000 years ago decided to utilize antique weaponry to bash a number of replica skulls to figure out which was most likely to be the cause of the passing.

We can benefit greatly from learning more about the skull, as it helped scientists to locate a case of archaic surgery gone wrong that seems to have ended up fatally for the patient. Trepanning, or drilling a large hole in the skull, has been practiced for thousands of years, and remarkably most patients survived the procedure, though obviously, not everyone did.